Holmes, Peirce, Gőbölyös & Co.

Holmes, Peirce, Gőbölyös & Co.

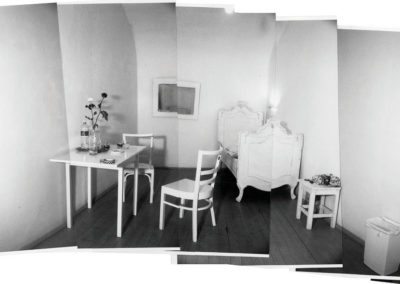

Where we are standing right now is a gallery. It is a gallery and the scene of an investigation. It is the place of an investigation, where – at least according to our knowledge – there hasn’t been a crime. Nothing, or rather, nothing outstanding has happened here. The only thing that happened here was that Luca Gőbölyös has turned the public space of the gallery into a private one; she monopolized it in order to transform it into a place which is the stage of her own life, her intimate sphere. Life itself and the small rituals of everyday life took the place of art. The location is the mixture of a hospital room and a Victorian girl’s room. A girl’s room which has been visibly stained by the traces of human bodies. It is both a gallery, a scene, a crime scene, a public space as well as a private one.

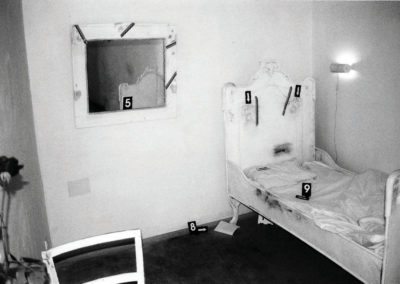

What has happened here can be figured out and reconstructed through all the police documents, examination records, investigation reports which are hanging from the walls. It is like a real concept exhibition, where the documentation is the work itself. However, here we also have this ghost ridden, archetypical girl’s room, or rather what is left of it. Here a question is raised ultimately: Is it possible to reconstruct what happened here in this impenetrable space which is now barricaded from us with a cordon? Is it possible to reconstruct the everyday? Is it possible to imagine the things which repeat themselves day by day; the banal habits? Things like someone combs her hair, stretches in bed, or stares ahead of herself inanely before she steps on the ground, blows her nose or perhaps searches for tissues.

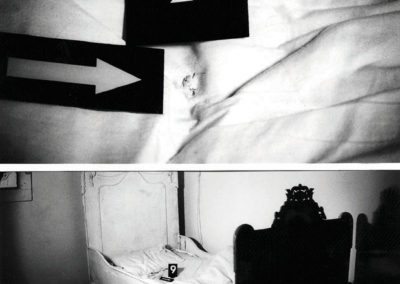

At this exhibition, the works are the traces of elements from Luca Gőbölyös’ everyday life. The documents of the investigation, the report, and the crime scene barricaded by the cordon are all works. One of the topoi of European culture which we have known since Horatius – that art is leaving traces for the sake of immortality, that the work itself is a monument more permanent than bronze – is the theme of this exhibition which becomes impertinently interpreted in a literal sense here.

Luca Gőbölyös’ all white girl’s room became dirty by the traces of her guests’ and her own body which was made visible. The bodies which were having wine here, and walked around a few days ago made this space dirty after their previously invisible traces were made visible. Making these visible, the presentation, the citation, and the discovering of the events and the truth come at a price: in our case, the price is that the white room was transformed into a pile of bluish grey spots, dirt, disturbing smears, off-white colors. Although it may not be indicated in the police report, but this is also a story. It is a story about how due to the activities and presence of a crime scene investigator who is empowered and has pledged to find out the truth – a man, in other words – has besmirched the honor of the white girl’s room.

However, as the detective in Poe’s famous short story The Murders in the Rue Morgue puts it: “it should not be so much asked ‘what has occurred,’ as ‘what has occurred that has never occurred before’.”

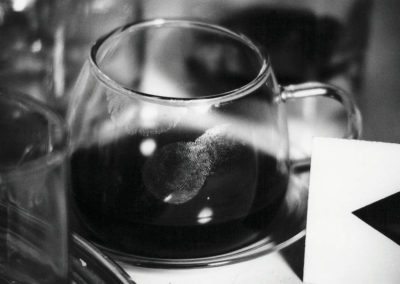

Luca Gőbölyös, a female Hungarian citizen, for the first, but perhaps not for the last time spent a few days in Stúdió Gallery, and according to the investigation report she did not leave the place at her own will. We are not talking about the Luca Gőbölyös here whose composite photograph can be seen on the exhibition’s invitation letter. We are talking about another one, the real one, about the young woman who has left her fingerprints all around the room. The distorted composite photograph which was made for the sake of identification resembles the woman who has lived here before, and the fingerprints are identical with the ones that the young woman who lived here had. One of them – the image – resembles her, but it could well be someone else. The fingerprint is unique and unmistakable, it is the thing itself; the trace of a life, a person, a body. The fingerprint is the symbol of identity. The presented work is the mixture of trace leaving, identification, and interpretation – just as all things associated with art are. Similarly to a crime scene investigator, the spectator also uncovers the story, life, identities, or phantasmagorias through the traces, through the work; to look for causes, effects, and connections, and to establish hypotheses.

Sherlock Holmes, Maigret, or Philip Marlowe reconstruct stories, characters and situations through the interpretation of signs and traces, and from the leftovers which are considered facts. The investigator from Budapest and the spectator is also after someone or something – as things always go: we are here in this world in the trail of someone, and we are the way we are, because of something or someone. Looking at this from Stúdió Gallery, the crime scene, leaving traces behind, looking for traces, and securing the evidence is nothing else but the metaphorical chain of art and life.

On the other hand, it is quite unlikely that a French police officer – who brought us the most revolutionary innovation in criminology – would have imagined his method as a metaphor of art, life, identity, and eternity. We are talking about Alphonse Bertillon, who introduced personal identification based on measurements and photography to the process of criminal investigation at the end of the 19th century in France and the first on the Continent to use fingerprints to solve a crime. Nevertheless, Bertillon discovered the same thing that poststructuralist art criticism did in the footsteps of American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce: that there is a good reason why we call the finger we point at things with index finger, the one which distinctly point to our identity, the index of the body part’s owner. The same as according to Pierce we also think of a large part of art as a sign, and within that as an index, which points at its signified not through similarities or conventions, but rather through interdependence.

The room which remembers and reminds us through traces of all those ever present there, the police files, the index finger, the place of the body, identity, art and semiotics, the finding of truth, life and the investigation obviously have a lot more to do with each other than we might think.

But we shouldn’t let the large span of concatenations misguide us, because we are on the wrong track if we do not know that there is always something which remains in the darkness. There always are mysteries which are untraceable. There always is a question, which is hard to find an answer for. In our case, this question goes like this: How did Luca Gőbölyös leave the room, if – as it could be read in the police report – she didn’t leave any footprints behind when exiting the room.

Ágnes Berecz

Exhibition opening of the exhibition In the Track of …,

Stúdió Galéria, Budapest, November 28 – December 22, 2000