Nude beyond Modernity

Nude beyond Modernity

Talking about nude and photo, Kenneth Clark explains that a photographed nude body in itself evokes an unpleasant sensation, due to the wrinkles, the loose skin, the fat and other irregularities, while the classical construction of the nude eliminates all these disturbing factors. Following tradition, he does not consider the nude a living organism, but a form of art. According to his argument, nature and reality are in opposition with art and the ideal, or in other words, art completes (corrects) nature’s work.

Though public perception of nudes has barely changed since the time when Clark described it in 1953 as a continuation of our culture’s antique heritage, these premises can hardly be used to with reference to the contemporary art of the nineties. Reevaluation was supported by tenets which began to analyse the questions of control over one’s body, and of whose point of view shapes the image and whose position of power is reflected by the visual representation. The flesh and blood body, together with its imperfections and deformities, has come to the foreground, while artists questioning the canon from the other direction began filling the void of the visual representation of the female body as viewed by the woman. While the need to ennoble and idealise the body originates from Antiquity, the need to control the body and suppress its physical side comes from the Judeo-Christian cultural heritage. The latter denies biological needs, considering the body unclean because of its desires, putting it in opposition with the soul, which it considers eternal. In Hungary, the Socialist system’s obsession with the elderly turned to gerontophobia following the political changes, and the American culture of future-orientedness, youth and health cult and the denial of death that follows has seeped in. The term “ageism”, meaning negative discrimination based on age, is hardly known, while its practice is common. Together with the political changes and economic globalization, the aggressive advertising and media politics of the new capitalist system have led to an abundance of idealised bodies associated with success.

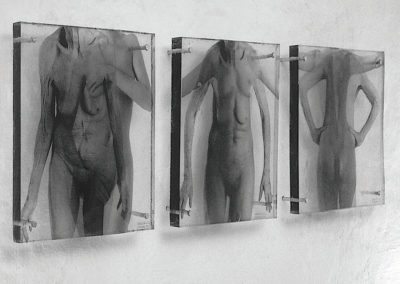

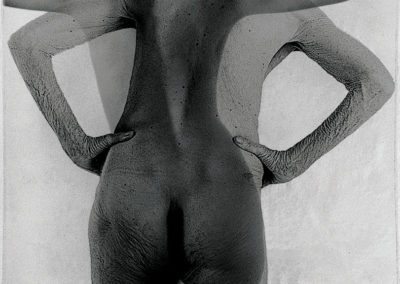

In accordance with this, we can barely find any visual representations of the aging body in contemporary art, and those of the aging female body are even more rare. In Luca Gőbölyös’s photo, showing an overlapping young and tight female body and a drooping elderly one, the artist confronts the viewer with the process of aging, removing the dimension of time. As if the transformation affected the same person, the tight contours loosen up, the back stoops, shoulders lean forward, breasts begin to hang in front of our eyes, just like in a horror movie or as the result of digital manipulation. In our age of belief in the omnipotence of science and technology, the crystal ball has been replaced by the X-ray (the photographic technique is in fact the same), the elixir of life by plastic surgery, and religion and beliefs by scientific authority. The direction of the process is not evident in the image, as the possibility of becoming young again, or at least the desire to, is also present. Another reading would be that the image is the beginning and end of adulthood, the entire life story flashing before our eyes in the moment before death.

In this end of the millennium Pygmalion story, this embodiment of ideal beauty, a motionless and timeless statue with a Medici Venus posture, metamorphoses into its alter ego. This alter ego is real, and carries the threat of passing away, as a living mockery of desires outside the limits of the body. The dual image with a double exposure puts the stable, eternal body image in opposition with the constantly changing living body; the ideal and perfect body with the unique, mortal one.

In our dual heritage culture, the hot blooded, passionate young woman embodies the hedonism and cult of body of Antiquity, while the dry and shrivelled body evokes the spiritual asceticism of the Middle Ages. The young woman demurely covers her genitals, an obvious reference to the innate erotic and sexual potential of all kinds of nude images. On the other hand, the naked body of the old woman is spread out in plain view, since her body evokes no erotic desires. Her hands fall drooping to her side, her legs are not closed tightly so as to preserve balance, and even her pubic hair is visible.

In our modern world, the image of the old woman is perhaps more of a memento mori, a signal of finality, a shadow of passing or the projection of a fear of death. In our dualist world view with a Judeo-Christian heritage, it is a fragile body doomed to mortality, as opposed to the eternally young soul. As we see no faces in the pictures, we cannot keep a distance and must confront our own aging and inevitable passing away.

Edit András

Revised, shortened version.

Published: Új Művészet, 2000/7, 20–23.