Our Everyday Saints

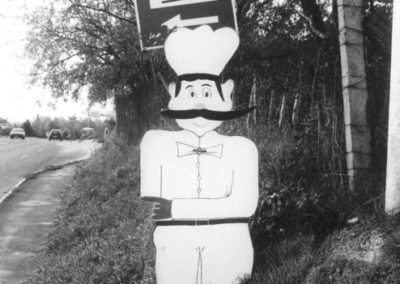

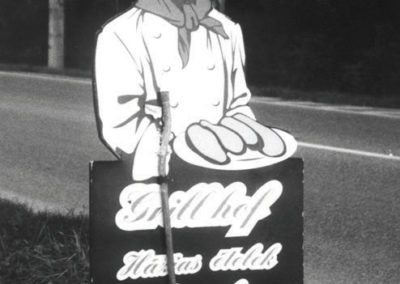

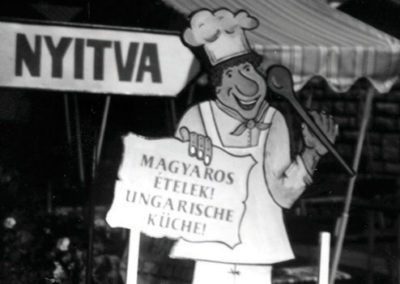

Let’s say we’re not at the opening of an exhibition, listening to the speaker. Instead, we’re sitting at the wheel, alone in the night and the familiar figures of pot bellied cooks and tipsy waiters show up in the headlights, cheerfully inviting us inside. So, we’re traveling, and people who are on the road tend to get hungry…

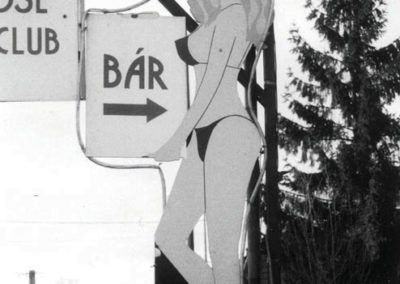

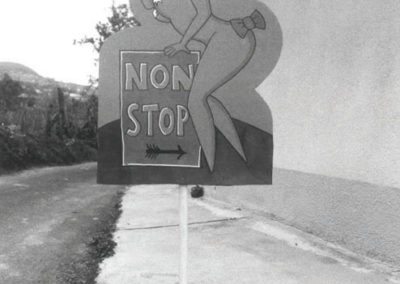

We can spend quite some time with Luca Gőbölyös’s works. Sometimes they make us laugh, sometimes they make us think, sometimes we are taken aback. They bring up an enormous amount of questions in the most natural way possible. This young woman has an astonishingly strange way of looking at things, and this leads to strange perspectives. The exhibition being opened now is yet another example that supports my argument. Let’s be honest: wouldn’t we all pass these cardboard creatures, appearing on the side of the road, without even thinking about them? Or should we consider them monsters? Well, let’s not go into this. Let’s not brush the phenomenon aside with some cheap bespattering, since ignoring these astonishing creations of our everyday decorative intentions would obscure their significance.

In this case, what is important is that through the use of relentless searching and collecting, the sheer amount is what shows us that which would otherwise go unnoticed: that this phenomenon has multiple meanings. These figures, seeping into our tired brains, are in fact present and affect our relationship with everyday visuality. Let’s not be so sure that they’re only clumsy advertising tactics, related to the laws of the market and to consumption. Instead, they show us the need for individual creativity. In fact, they’re a form of folk art (which tells us a lot about the current situation), and in such great numbers, they show us a broad spectrum of our most basic stereotypes. Are they really our roadside patron saints?

Luca Gőbölyös approaches the spaces and institutions of contemporary art from an unusual angle. She plays with space in a paradox manner, pretending to present a mere documentation of her collection, while evoking a situation, the experience of travel.

At other times, she treats exhibition spaces in a brazen way. She moves into galleries (this is what happened last year at Stúdio Galéria, Budapest), setting up a Victorian girl’s room, in order to live her everyday life and to leave her mark among the white walls meant for high culture. Later, she calls the police to find the traces one leaves while simply existing, and lets the police create a story, a narrative, based on the clues. Finally, from among the fingerprints and the „evidence”, the person herself appears.

Here too, we can make out a curious and cheeky gaze, who searches and collects without any clues, then puts the traces and symbols together, talking about us with ease, but even more so, asking, asking, and asking…

Edit Molnár

Exhibition opening, Hungarian Cultural Institute,

Bucharest, November 2001

On the Side of the Plate

Trafó Gallery, Budapest

It wasn’t just the aspect of gastronomy that caused Luca Gőbölyös’s and HINTS Artist Association members’ (Eszter Ágnes Szabó and Mónika Bálint) works to be exhibited beside each other at the Trafó Exhibition. The exhibition examines social customs and phenomena related to dining, but only from the side of the field, or rather, the plate. Luca Gőbölyös has been photographing the advertising signs of restaurants, roadhouses, pubs, cafeterias, and bars. It’s quite a fruitful topic. The clod chefs and well-mannered waiters put their imagined selves beside the road, with two dimensional signs usually resembling a caricature. Gőbölyös does nothing more than lining up these figures, although she does accompany them with an occasional cultural, anthropological, or sociological footnote. She compares the advertising sign figures to roadside tin Jesuses and saints. And they do stand there like patron saints of eating. She adds that female figures are only found in front of places offering erotic services, but never in front of family restaurants. The creators of the tin signs didn’t imagine women with long legs to be working in kitchens. Or, to be precise, they believe that travelers are more like to stop for lunch when invited by a jovial chef, than if by a frivolous missy. Maybe so. Though there would be a place for a kitchen nanny with a spotted scarf and a wooden spoon. But no, these signs continue the iconography of cheap caricatures, joke books and lewd cartoons. The world can be divided into loser husbands, wives with shopping bags, overweight bartenders and lovers with long fingernails. Doesn’t the Hungarian man ever forget these stereotypes, not even before, during or after eating? Do we do the same around the table that we do in any other part of life?

Nagy Gergely

Revised, shortened version.

Published: Műértő, 2002/5, 6.