The Representation of Remembrance

The Representation of Remembrance

– For Luca Gőbölyös’ Work

Luca Gőbölyös deals with memories and remembrance. Besides the representation of the structure and mode of remembrance – and the visual analysis of all that – she also asks important questions about photography itself.

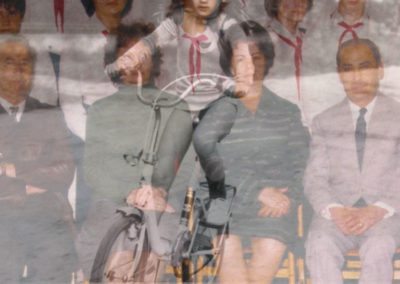

Therefore, the medium she uses to accomplish this also bears a special importance. Lenticular press technology enables precisely that method through which it can be presented how the different layers of remembrance settle on each other, how they cover or uncover the information carried within different types of mediums.

The work of Luca Gőbölyös is not only aimed at the investigation of the structure of remembrance, but also at demonstrating those contradictions which lie in between the lived, the experienced and memories told by others later on. In the interpretation of Susan Sontag, the photograph is not there to help preserves memories, but to speed up and stimulate the process of forgetting. If the photograph is available, there is no need to practice other forms of remembrance anymore, as the image replaces everything in itself, and it helps to recall long forgotten feelings. The photograph, which even today has a strong magical function, transforms and overwrites other components of remembrance with its seemingly conclusive content. It is this contradiction which prompts Roland Barthes to face the photograph as a problem, when he finds a photograph of his recently passed mother where she is only sixteen. Here, the corroboration turns into its exact opposite, if the possibility of transmission gets lost between the image secured by the memory, and between the sight of the physical image which presents itself as real. Therefore, the photograph can often step into the place of remembrance, and can even provide a foundation for it, in case a state of complete forgetting has been reached in connection with the one depicted on the picture.

In many cases a strange situation can occur due to the fact, that the photographs which visualize something that is no longer part of the memory and include memory concepts of preserved and new content, are no longer portable, they are no longer compatible and/or verifiable with anything else. If we accept the visible information, and we transfer it to our memories, than we can only do that for its own sake. Of course, in the work of Luca Gőbölyös the photograph – according to its purpose – cannot be in such an absolute position. She directs the attention to the notion, that – generally speaking – the photograph cannot be identical with the memory – and as a refutation of Sontag – she points to the fact that photographs cannot be substitutes of memories; photos are merely a peculiar aspect of them in the process of remembering. The chosen technical solution also goes against this unifacial and two-dimensional approach, by emphasizing the layered arrangement and complexity of memories. These images recall an era when the maintaining of illusions and hypocrisy played a crucial role in survival tactics. An era when one could only find a possible way out from its compulsions through a real or a symbolic withdrawal, by keeping a distance from it. This attitude can easily be traced in the different photos that constitute the basis of the work. A section of it is from the family album; they are connected to intimate or emotionally important moments, presumably taken by one of the parents. The other pictures – an ID photo, or the photos from school – were ordered by an institution, and an official photographer took them. Therefore, these later ones strengthen the self-representation of the system, and they become instruments of that. The counter-positioning of the two types is obvious. The conflict that stretches between the two – despite its importance – is perhaps less explicit. The family photo is spontaneous; it is connected to a concrete situation or moment. The mood of the moment, its richness in emotions or the event itself reasons its creation. The school photograph works the opposite way around and it wants to express its contradictory position. It wants to overwrite and neutralize these images – which are interpreted in the context of the private space – with its own system of codes, and thereby interfering with the process of remembering. Even if these photographs represent an actual person, in terms of their essence, they are aimed at making the self-representation – within the cultural and social discourse – of the dominating power of the time palpable.

However, considering the essence of remembering; the process is never visual, but discursive. The images – which stand by themselves as evidence – are not able to fulfill any kind of role in the process of remembering by themselves, which can only be carried out by engaging in different kinds of communicational acts in given social groups where they are embedded. The instrument of this is verbal expression.

The texts cannot be considered descriptive in connection to the image, and they are not interpretations of them. Despite this, they are inseparable, their collective presence is justified, they are not accidental and random; their linkage becomes organic through the process of remembering. Partially, these visualized, textualized thoughts present the short summaries of such stories which the author has experienced, and in part they are such “quotations” which she could only have heard about from someone else. Therefore, they can only be an indirect part of her memory, although they are seemingly completely integrated with that. The images are in contradiction to these texts, which – in all cases – represent a part of someone else’s remembrance, and they can only become part of the author’s memories through a process of communication.

The work is therefore mainly a facing of herself, with her own memories through the images of other people. These private memories either get support or are refuted – they fade away – in the medium of communication. But what happens, if we stick to the ones secured in our own memory, if we are not concerned about the support or the refute? Are we allowed to do anything with them as we wish? And finally: How does this mechanism get started in case of the receiver who is forced to face his own past, his own memories through the memories of someone else?

Gábor Pfisztner

Revised, shortened version

Published in: Fotóművészet, 2007/1, 25-27

Complicity?

Complicity?

Luca Gőbölyös’ series from 2006 made with lenticular technique, uses her personal photo archive; images from her childhood about herself and her family. Every single piece contains several photos, which – according to the characteristics of the surface composed of lenses, and depending on the angle of light hitting its surface – appear either permeating through each other or just by themselves. Applying this technique – typically used in the 70s – is not only reasonable because the images are also from this era, but also because it resembles the dual nature of memory: things that we forget often disappear suddenly and without a trace, but later they flash back at us again intensively and unexpectedly. Although the text accompanying the photos report on actual personal memories – similarly to images – they also work on the level of common consciousness: the childhood photos and memories are similar for many of us who lived in this region at the time. Despite recalling the socialist past, the series is not “nostalgic” – as it is often the case with works that relate to this era. Rather, we could label it as “progressive nostalgia” (using the term coined by Viktor Misiano), as Gőbölyös connects the events of her own past with the political practices of the time – which should be handled critically – and confronts them with everyday life.

Erzsébet Pilinger

Revised, shortened version

Published: on the Atr Fanatics exhibition