BARBIE OPENING - 'LIFE IS YOUR CREATION'

BARBIE OPENING – ‘LIFE IS YOUR CREATION’

(PH Gallery, 16 December 2023)

REALITY AND ITS BARBIE COUNTERPART

As long as there have been humans, there have been dolls. Doll and man, man and doll are inseparable. There’s something astonishing, something human, so to speak. That we need something to reflect on our own form, and even on creation and the world itself. We create something that, however tenuously, resembles the act of creating man. We create something, someone, that is like us, we mould it in our own image, but we are not. Or, in certain ritual cases, we are. The BABA is the eternal, prominent Substitute. In varying forms and with varying purposes and motivations, humanity dolls itself unceasingly. Apparently, the baby is a must. It’s always for something else, but it’s a must. Whether it be magic, voodoo, or a training tool for future motherhood, sex, fashion, robotics, religious, ritualistic, mannequin, fashion doll, ideal doll, i.e. model. And a model can be a representation of something real in miniature, but it can also be a devilish or angelic design, something that is a visual representation of a design or idea that is to be created or will be created. Or it can be a combination of the two, like Barbie, who is 64 years old this year.

I was about seven when I got my first Barbie. It must have been the second set, because she could bend her knees (YUM!!), which I was so proud of, and of course, it made her pose better. But Barbie can not only pose, she is also a pose, a cultural pose, an artificial will that performs the image of the ideal, perfect woman – in a given age. After the company Mattel, which produced Barbie during the first wave of feminism, came under heavy criticism, they tried to replace the prescriptive Barbie image, which was unattainable because of its perfection and excluded the image of the everyday woman, with more inclusive versions. Black and brunette Barbie, pregnant Barbie (who never gives birth), pilot and president Barbie, and, most recently, Barbie in a wheelchair and prosthetic limbs, as well as real-life female role models. You can, so to speak, play with these possibilities, even if they are often far from reality.

A few years after Barbie’s birth in 1959, by popular demand, her side-child Ken was created. Barbie’s inventor/developer Ruth Handler named the dolls after her own children, Barbara and Kenneth, but for obvious marketing reasons, she kept Barbie in the forefront. Ken is thus presented as Barbie’s accessory, like a pretty handbag or high heeled shoes. In this way, ironically, the power structure known and familiar from real life is exceptionally inverted: Ken is presented as an oppressed, repressed minority, which Barbie uses at most for representational purposes (see Ryan Gosling, who plays Kent, the amusingly chatty, shagging, Kent in the Barbie film). Dreamland here, for once, presents not only an unattainable possibility, but one that seems real. You can be a CEO, an astronaut, a president, a Nobel Prize-winning scientist, or simply a single person who is not bound by obligatory gender roles, who does not start a family, who is free to decide his or her own destiny – or, at least, who helps to play the act of free choice. But what happens to Kennel, who in Barbieland plays the role of a marginalised, ‘objectified’, powerless minority?

This question is explored in the photographs of Luca Gőbölyös, who goes back to her 1996 exhibition “Untitled”, the first in Hungary to depict and publicise a social group, the previously invisible trans community. The change of political regime has also brought a change of visual art regime, but in the neo-prescriptive and prohibitive, censoring context of the present, it is worth examining how this retrograde, restorative process can be represented in the visual means of the present. That is, how to describe the artistic and political representation of the queer community from the regime change to the present. Particularly in a political climate in which books with even a trace of LGBTQ content can be ripped up, shredded, foiled, and those under eighteen can be banned from the National Museum without a problem. So, as usual, dictatorial power acts as censor of vision, of visibility – business as usual, nothing to see here.

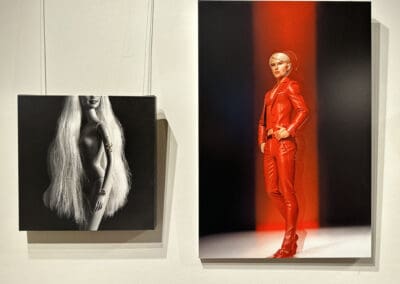

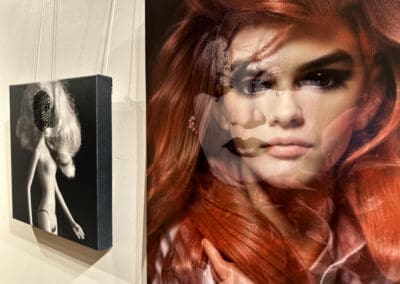

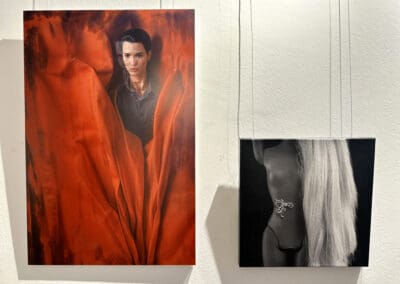

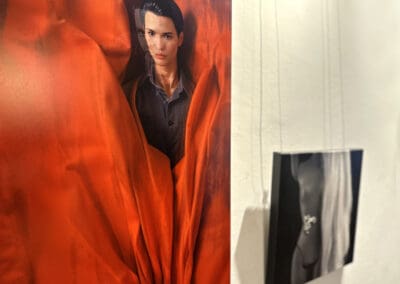

In Gőbölyös’s photographs, the real models of the ’96 exhibition appear as ghost images in the background of Ken figures created with AI technology and even more depersonalised, who as trans people have already gone through a transformation, crossing the boundaries of gender identity in their visual self-representation, transforming themselves into someone other than what their social and gender role would dictate. They perform an idealised image of womanhood, the imagined essence of femininity, with ironic, self-reflexive exaggerations. They hover here behind the artificial AI-Kenes, like Hamlet behind, above the ghost of his father. AI Ken (on the model of GI Joe) is the new, post-postmodern, plastic Hamlet. Plastic as a material, without depth or character, is also an important element in the photo-based works of another artist in the exhibition, Suzanne Nagy, who re-personalises, eroticises, possesses and defiantly-weakly-uniques the plastic Barbie bodies with patterns, quasi “tattoos”, embroidered on them by herself.

Barbie is no longer just a toy, but a pop cultural icon. In this exhibition, she also becomes a political icon, reflecting not only the current power dynamic, but also the new visual technologies that are taking shape and emerging. On the threshold of AI, VR, HOLOGRAMM, AVATAR, DEEP FAKE, or fake culture, a new surrealism is unfolding, one that is as much bound to the reality it feeds into as it is divorced from it. After a postmodern culture that focused on surface rather than depth, recent visual techniques seek to transpose this surface back into ‘depth’, creating multiple cultural and visual ghosts. Does the re-transformation of transformation bring us back to the original? But the notion of originality has long since disintegrated; new layers of ghostly images are formed, and in time, obviously, they too will disappear. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain – as Roy the android says in The Winged Bounty Hunter. But the Hamlet question of the present, posed in a slightly different light, is more topical than ever: to be or not to be? That is the question. Poor Barbie, poor Ken, who just wanted to play.

Zsófia Bán

BARBIE MEGNYITÓ – ’LIFE IS YOUR CREATION’

(PH Galéria, 2023. december 16.)

A VALÓSÁG ÉS ANNAK BARBIE MÁSSA

Amióta ember létezik, azóta van baba is. Baba és ember, ember és baba elválaszthatatlanok. Van ebben valami megejtő, valami, úgyszólván, emberi. Hogy kell valami, amivel saját alakunkra, sőt, magára a teremtésre és a világra reflektálunk. Létrehozunk valamit, ami, ha gyarló módon is, hasonlít az ember teremtésének aktusára. Létrehozunk valamit, valakit, ami/aki olyan, mint mi, a saját képünkre formáljuk, de nem az vagyunk. Illetve, bizonyos rituális esetekben, mégis. A BABA az örök, kiemelt Helyettes. Váltakozó formákban és váltakozó célokkal, motivációkkal, rendületlenül babázik az emberiség. Láthatóan, a baba kell. Mindig másra kell, de kell. Legyen az varázslat, vudu, vagy gyakorlóeszköz a majdani anyasághoz, szex, divat, robotika, vallási, rituális kegytárgy, próbababa, divatbaba, ideálbaba, azaz modell. Egy modell pedig lehet valami valóságos dolog leképezése kicsinyített formában, de lehet ördögi avagy angyali terv is, valami, ami egy majdan létrejövő vagy létrehozandó tervnek, ideának a vizuális megjelenítése. Vagy lehet a kettő kombinációja, mint például, az idén hatvannégy éves Barbie.

Olyan hét éves lehettem, amikor megkaptam az első Barbie-mat. Talán a második széria lehetett, mert már a térdét is be tudta hajlítani (ÍME!!), erre iszonyú büszke voltam, és persze, így jobban lehetett pózoltatni. A Barbie azonban nem csak pózolni tud, hanem ő maga is póz, egy kulturális póz, egy művi akarat, amely az ideális, tökéletes nő képét performálja – egy adott korban. Miután a feminizmus első hulláma alatt súlyos kritikákat kapott a Barbie-t gyártó, Mattel cég, igyekeztek a preskriptív, és a tökéletessége okán elérhetetlen, a mindennapi nőképet kizáró Barbie image helyett, inkluzívabb variánsokat a piacra dobni. Fekete és barna Barbie, terhes Barbie (aki végül soha nem szül), pilóta és államelnök Barbie, végül, legújabban, kerekes székes és művégtagos Barbie, valamint valóságos, női példaképeket megformáló Barbie-k. Úgyszólván, el lehet játszani ezekkel a lehetőségekkel, még ha a valóságtól sokszor távol állnak is.

Barbie 1959-es születése után néhány évvel, közkívánatra, mintegy az ő oldalbordájából, létrejött fiúpárja, Ken. A Barbie babát feltaláló/kifejlesztő Ruth Handler a saját gyermekei, Barbara és Kenneth után nevezte el a babákat, de –nyilvánvaló marketing okokból – a kiemelt pozíciót meghagyta Barbie-nak. Ken így mintegy Barbie accessoire-jaként van jelen, mint egy szép retikül vagy magassarkú cipő. Így, itt ironikus módon, kivételesen megfordul a való életből ismert és megszokott hatalmi struktúra: Ken elnyomott, eltűrt kisebbségként szerepel, akit Barbie maximum reprezentációs célokra használ (lásd a Barbie-filmben mulatságosan csetlő-botló, Kent alakító Ryan Goslingot). A Dreamland itt kivételesen nem csak egy elérhetetlen, hanem egy valóságosnak tűnő lehetőséget mutat fel. Lehet cégvezető, űrhajós, államelnök vagy Nobel-díjas tudós, vagy egyszerűen csak szingli, akit nem kötnek a kötelező társadalmi nemi szerepek, nem alapít családot, szabadon dönt a sorsa felől – illetve, segít legalább eljátszani a szabad döntés aktusát is. De mi történik mindeközben Kennel, aki Barbielandben a háttérbe szorított, “tárgyiasított”, hatalom nélküli kisebbség szerepét tölti be?

Ezt a kérdést járják körül Gőbölyös Luca itt látható fotói, aki visszanyúl 1996-os “Untitled” című kiállításának anyagához, amellyel Magyarosrszágon először ábrázolt és tett publikussá egy társadalmi csoportot, a transzok addig láthatatlanságra ítélt közösségét. A politikai rendszerváltás egy vizuális művészeti rendszerváltást is hozott, azonban a jelen neopreskriptív és tiltó, cenzúrázó kontextusában érdemes megvizsgálni, miként lehet ezt a mostani retrográd, restauratív folyamatot a jelen vizuális eszközeivel megjeleníteni. Azaz, miként írható le a queer közösség művészeti és politikai reprezentációja a rendszerváltástól máig. Különös tekintettel arra a politikai klímára, amelyben, akár csak nyomokban is LMBTQ tartalmú könyveket gond nélkül szét lehet tépni, le lehet darálni, le lehet fóliázni, és a Nemzet Múzeumából tizennyolc éven alúliakat ki lehet tiltani. A diktatorikus hatalom tehát, szokás szerint, a látás, a láthatóság cenzoraként lép fel – business as usual, nincs itt semmi látnivaló.

Gőbölyös fotóin az AI technológiával kreált, és még jobban deperszonalizált Ken figurák hátterében, szellemképként megjelennek a ’96-os kiállítás valóságos modelljei, akik transzként már eleve átmentek egy transzformáción, vizuális önreprezentációjukban átlépték a nemi identitás határait, átformálták magukat valaki mássá, mint akit a társadalmi és nemi szerepük előírna nekik. Egy idealizált nőképet, a nőiség elképzelt esszenciáját performálják ironikus, önreflektív túlzásokkal megtoldva. Ők lebegnek itt a művi AI-Kenek mögött, mint Hamlet mögött, fölött atyjának szelleme. Az AI Ken (a GI Joe mintájára) az új, poszt-posztmodern, plasztik Hamlet. A mélység és karakter nélküli plasztik, mint anyag, fontos eleme a kiállítás másik művésze, Suzanne Nagy fotó alapú munkáinak is, aki a plasztik Barbie- testeket a saját maga által rájuk hímzett mintákkal, kvázi, „tetoválásokkal” reperszonalizálja, erotizálja, birtokba veszi és dacosan-gyengéden egyedivé teszi őket.

Barbie már régen nem csupán egy játékszer, hanem egy pop kulturális ikon. Ezen a kiállításon politikai ikonná is válik, amely nem csupán az aktuális hatalmi diksurzusra, hanem a most formálódó és kibontakozó, új vizuális technológiákra is reflektál. Az AI, VR, HOLOGRAMM, AVATAR, DEEP FAKE, azaz a fake-kultúra küszöbén, egy új szürrealizmus van kibontakozóban, amely legalább annyira kötődik a beléjük táplált valósághoz, mint amennyire el is rugaszkodik tőle. A posztmodern kultúra után, amely a mélység helyett, a felületre koncentrált, a legújabb vizuális technikák ezt a felületet igyekeznek ismét „mélységgé” transzponálni, ezzel többszörös kulturális és vizuális szellemképeket kreálva. Vajon a transzformáció újratranszformálása visszavisz az eredetihez? Csakhogy az eredetiség fogalma már jó ideje szertetfoszlott; újabb és újabb, egymásra rakódó, szellemképes rétegek képződnek, aztán idővel, nyilván ezek is eltűnnek. All those moments will be lost in time, like tears in rain – ahogy Roy, az android mondja a Szárnyas fejvadászban. A jelen, kissé más fénytörésében feltett, hamleti kérdése azonban, aktuálisabb mint valaha: lenni vagy nem lenni? Ez itt a kérdés. Szegény Barbie, szegény Ken, akik pedig csak játszani akartak.