Nude beyond modernity

Nude beyond modernity

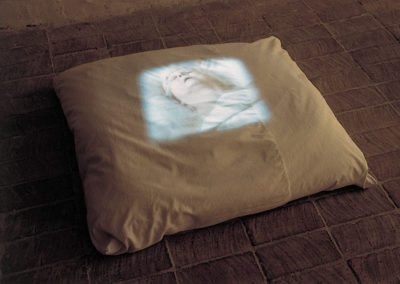

The video installation deals with metamorphosis, balancing, and sometimes transgressing the borderline between life and death. The reason that viewers of this video installation are taken aback is that they seem to recognize the moment of passing. The association is strengthened by the naked, helpless body, the head sinking into the pillow, the closed eyelids and open mouth, and the far from favorable angle (a photo taken from below) which reminds us of cadaver photos. We can only hear the rhythmic breathing in total silence. We see an unknown old woman, an antihero, during the anti-heroic act of sleeping; an intimate and personal moment in a public space.

The bare light bulb hanging above the table and the outspread body evokes the image of a mortuary, as if the cadaver’s body has been pressed through the shroud. The fruits on the table carry the association of a dining table, while in connection to death; they remind us of the banquet above the martyr’s grave, the momentary symbiosis of life and death, the place of the banquet of remembrance shared with the dead. But what we see is not the dead body of the martyr who died for her beliefs, soon to become a saint with an altar, and later with a church raised above her remains, but instead an old woman, defenseless in her nakedness and old age, spread out helplessly with hanging shoulders and head. The food is not bread or wine, for the mystical unification with God, but instead an apple, the symbol of seduction, sensuality, and the Fall, which is attributed to women. The punishment for the desires of the flesh, ageing and dying, is presented visually by putting forth the grave consequences, without any beautification.

The visual presentation of scientific and medical discourse is present in the work, in the way that it rationalizes and objectifies the body in order to remove it from the concerns of the living. With the dissection images, we don’t identify with the cadaver, which could be the remains of an old man: though the scene is shocking, it does not evoke the fear of death, thanks to the distancing.

Manabu Yamanaka’s nude photos of skeleton-like Japanese women of ages around 100 are the international counterparts of these works. As opposed to John Coplans, who presents his own ageing and deforming body on gigantic photos, they both are outsiders, voyeurs. But while Yamanaka’s photos are without compassion and empathy, isolating the ageing female body in a vacuum to make it seem grotesque, Luca Gőbölyös does not lift them out of their social environment and the web of cultural connotations they are embedded in, but instead confronts the old body, denied, looked down upon, and viewed as shameful, with these connotations. And since she is a woman photographing old women, her empathy is visible in these photos. The works are unsettling and emotionally moving, but not grotesque or merciless, as she cannot and does not wish to take up the position of the outsider.

Edit András

Revised, shortened version.

Published: Új Művészet, 2000/7.

The Taming of the You

The Taming of the You

At Luca Gőbölyös’ most recent exhibition, we can once again view a favorite corpus of ours, the taming of the shrew. Not the piece, of course, but the woman herself (a piece of woman), or more precisely her body: her corpus. Yet, this woman is just as much of a shrew as the original; moreover, she is shrewd as well. She is also extremely wrinkled, or to use the term popular in our culture: she is old. It is, however, also a popular view in our culture that to show something like that is not polite, at least not for esthetic purposes. So then, we are inclined to ask, what is polite to show in our culture? It is polite to paint old women for allegorical purposes (Death, Mortality & Co.); it is polite to offer a literary representation of the old woman as witch, evil spirit or villain; it is polite to photograph old women (but only from foreign lands and preferably very distant continents!) for anthropological and colonizing purposes; it is polite to exhibit old women with bizarre bodily features as freaks at the circus; and finally, in this culture that worships the ideal of youth, it is polite to display the aging female body as an instance of horrifying and warning grotesque. It is, however, not polite to present shrewd old shrews, who obviously refuse to respect these rules and who are willing to display their bodies in public in their fully realized and evolved form for the sole purpose of allowing us to read these bodies as some kind of shriveled and ancient encoded text whose decoded form reveals life itself – their life and ours.

But this is precisely what Luca Gőbölyös’ images do: they transgress these carefully delineated borders which, like the trapeze artist’s net, protect this culture obsessed with body control. Gőbölyös jumps without a net, and this is not without its danger for the viewers either. For her works make us witness the moment when – caught in the act – old age is transformed from topos or metaphor into reality. Despite this (i.e. despite “reality”) the confrontation is still carried out with the means of art – and this is what makes it a real feat. The implied danger for the viewers in all of this is that we cannot distance ourselves from these images, there is no room to back up, and should we try to, we can only bump into our own selves. The gaze that forms the image here is not that of an outsider; it could easily be our own in our most intimate moments. In moments that are usually not public, but which here and now have become public, and this is what is so terribly difficult to bear. For what can be more intimate than being confronted with our own (headless) aged body pressed under glass for conservation, like an item in a rare insect-collection? Or the moment when we observe the sleep of an old woman (ourselves, our mother, our grandmother) and we are suddenly overcome by that anxiety familiar to all: is she still breathing? (If we lean close to the pillow we can hear that she still is.) Or the moment when we watch over our dead laid out (in this case, literally) and then remember them by a laid table, consuming the experience of death?

It is well known that many people experience the violation of their intimate sphere as trauma, and in this sense Gőbölyös’ works are traumatic, but they are also cathartic. They help us learn another kind of seeing which makes our gaze more open, more accepting and closer to life. They help us rid ourselves (at least temporarily) of the terror of seeing and representation in the process of the taming of the You. They help us learn to read other kinds of texts, other kinds of writing; moreover, they help us recognize their textuality in the first place. Finally, instead of (or besides) the esthetics of absence they help us acknowledge and accept the esthetics of presence. These are some of the things the shrew can do.

Zsófia Bán

Published: [catalogue] Óbudai Társaskör Galéria, Budapest, 2000.

Representation of the Body

Representation of the Body

in Contemporary Hungarian Art

Challenging taboos is behind her work in which she develops photos of naked body parts onto the surface of transparent shop window mannequins used for displaying underwear. These boosts are faceless, impersonal fragments locked up in an old wardrobe. By opening its door, a carefully hidden secret is revealed. By this an ambivalent attitude to the body is expressed: it must be hidden from sight. What we are faced is the embodied Other whom we can only access by peeping into the secret of others. In our culture there are certain unpleasant, shameful feelings connected with the body. Detachment from reality and a fetishlike quality of the work are reinforced by the projection of body fragments onto a female fetish object related to underwear. The photo emulsion appears on a transparent plastic surface, thus endowing the photographic image with an ephemeral, evanescent character, by which the body is transformed into an illusion, an image of desire as opposed to a reflection of flesh-and-blood reality. The fact that the artist chooses mannequins to convey these messages adds yet another level of connotation to her work – the objectification and eroticization of women, in a low-tech-medium, such as a shop window mannequin.

Edit András

Revised, shortened version.

Published: In: Erotics and Sexuality in Hungarian Art,

Független Képzőművészeti Műhelyek Ligája, Budapest, 1999./ 49–81